Data, Design & Ethics

- Data Ethics ·

- Design Practice

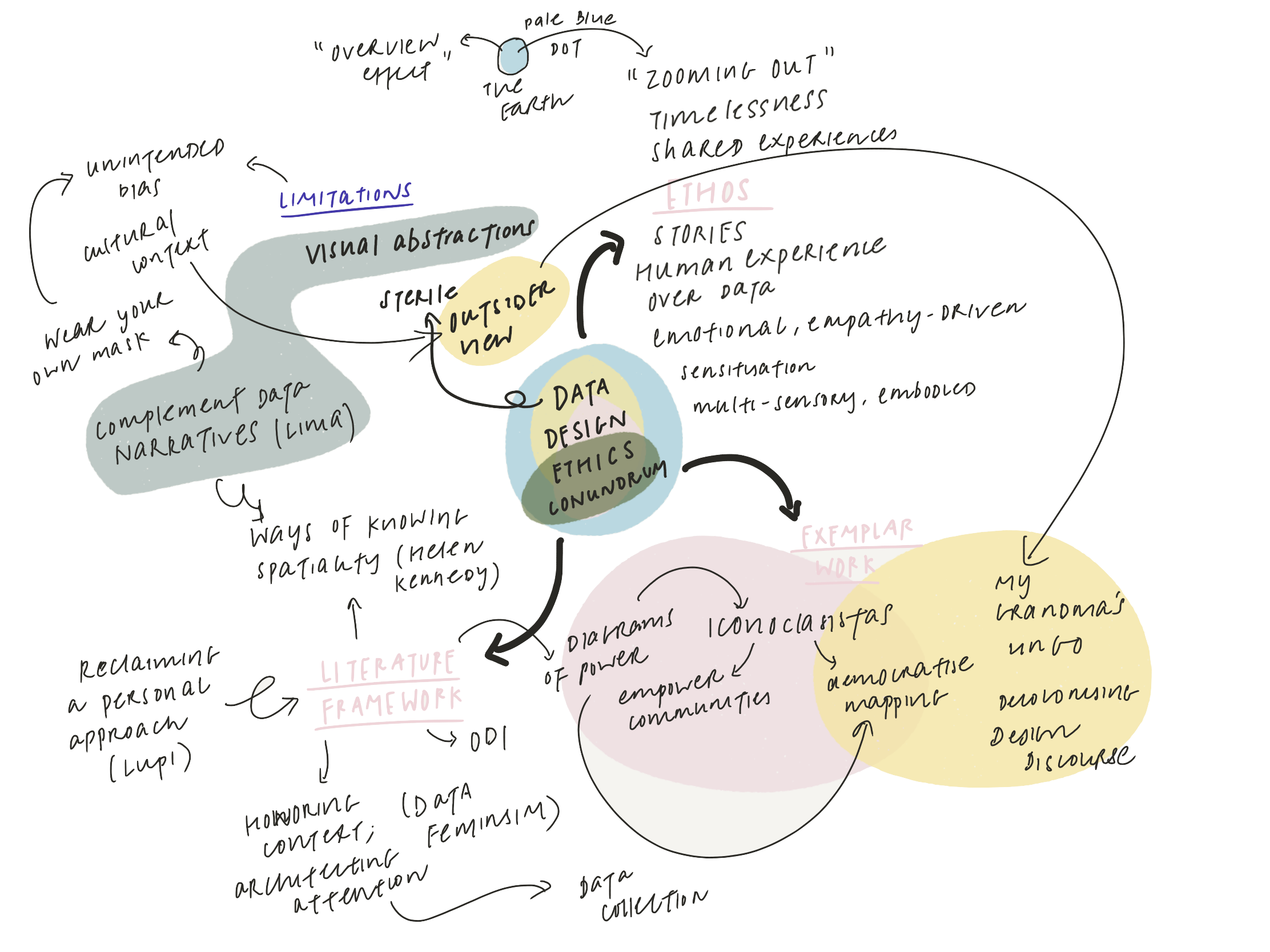

Astronauts, on their first sighting of Earth from outer space, describe an overwhelming awe when confronted with the beauty and fragility of human life on a pale blue dot against the backdrop of a dark and hostile cosmos. Dubbed the overview effect (White, 1987) [1], this cognitive shift changes their sense of self and value system.

Human-centric forms of communication, including visualisation, strive for timelessness, to transcend barriers of borders and languages to unify us in meaningful ways through our shared, universal experiences. The dramatic perspective afforded by space travel is, of course beyond reach for most design projects, however, emotional engagement remains essential for forging meaningful connections.

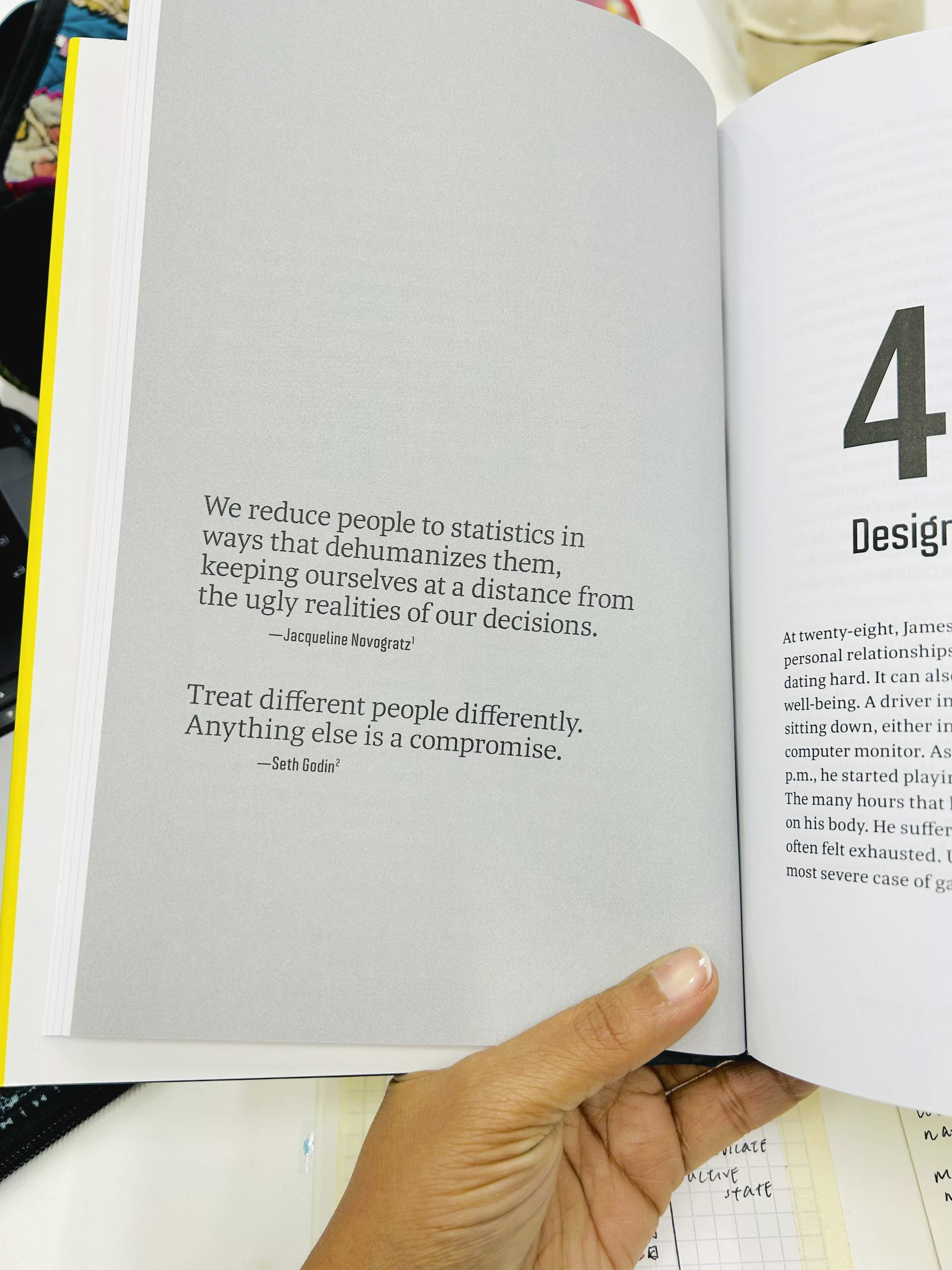

Sadly, data visualisations don’t always engage us at an emotional level or inspire empathy, and this happens for several reasons. As multi-sensory beings, we naturally perceive and understand the world in spatial terms [2], and visual abstractions, such as data visualisations, can create a sense of detachment from our real- world physical experiences [3]. Further, a sterile focus on data and objective measurements, particularly when dealing with data about human experience, creates a form of desensitisation and moral disengagement [3].

Practitioners have sought different means to tackle this issue, by “reclaiming a personal approach to how data is captured, analysed and displayed” [4], focusing on “honoring context & architecting attention” [5], and stressing the value of incorporating narratives alongside visualisations to complement facts and figures [3].

In my work, I draw from a similar position by treating subjective experiences as legitimate form of data and embracing expressive forms of visualisation. Manuel Lima’s idea of the adage “putting on your own mask” [3] describes my approach to addressing unconscious biases. I am conscious that my design education has been predominantly Western & European-centric, which often neglect the plurality of perspectives from other parts of the world, particularly the non-English speaking world. I understand my position as an outsider and the institutional and personal walled gardens of my experiences make me susceptible to unintended biases and monocultural perspectives. This may limit what I notice or prioritise. For this reason, I seek to engage with a diversity of perspectives through participation and by inviting others into my process. Nonetheless, I also recognise the inherent value of an outsider’s viewpoint when approached reflexively.

My interest lies in what such a shift in perspective makes possible. The value of distance, in this sense, is not detachment but a means for recognising how position, scale, and abstraction shape what is seen, prioritised, and acted upon. Data visualisation, like any representational practice, is never neutral. It encodes decisions [6] about what is rendered invisible, and how relationships are framed. An ethical approach, then, is less about prescribing correct outcomes and more about cultivating awareness of these conditions. It requires repecting context and an acknowledgement of partiality.