Media, Affordances, and Expressive Typography

The history of poetry and use of poetic text in expressive typography is entangled with the parallel evolution of technology and media. Before the invention of printing, poetry was largely capturing an oral culture. Words, structured into poems, were used as markers to perpetuate stories, events and emotions. The use of rhyme and rhythm, the breakdown into groups of lines forming verses were devices invented to allow poetry to be easily remembered and understood.

Any communication effort presupposes the existence of a communication medium. The vast majority of typography’s history focused on static presentation media like print and sculpture. Printing brought the first major change in how poetry was created and distributed. The use of physical processes like letterpress and photo typesetting brought about a surge of exploration pushing layout and compositional techniques. This period of intense exploration led to the development of conceptual tools, terminology and models for designing and describing typographic attributes in print media.

For the purpose of contextualising the evolution of expressive typography, it is useful to classify presentation media into three categories: static, temporal and interactive media. Static presentation media like print, came into existence early and hold the richest collection of experimentation and academic study of typographic forms. Typography flourished in print-based media and established itself as an essential tool for visual communication.

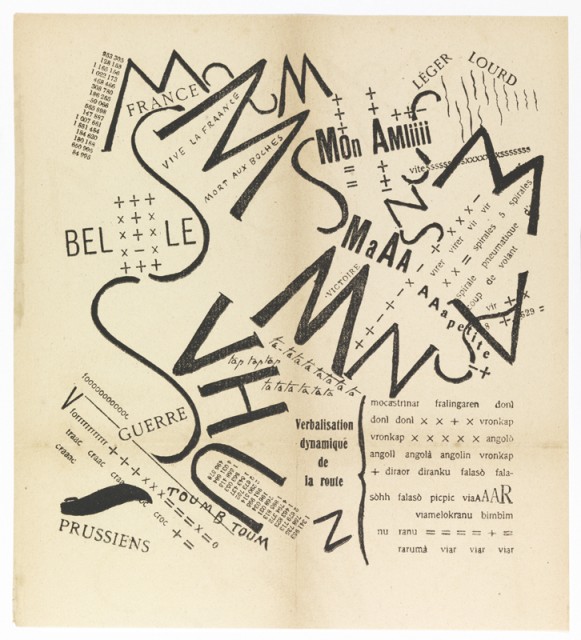

While static typography is fundamentally focused on a fixed presentation, experimental typographers pushed the boundaries by manipulating letterforms in varied ways and introducing the analogies of motion in type. This line of experimentation is most clearly seen in the works of the Futurists and other Concrete poets like F. T. Marinetti and Ian Hamilton Finlay who deconstructed linear writing, expressing meaning through size, weight and placement while encouraging readers to marshal all their senses to experience the poetic text.

With the introduction of film and television in the 1950s, designers began to experiment with time-varying or temporal presentation of type. Temporal media expanded the potential of expressive typography by enabling typographic forms to evolve over time. Pioneering work by Saul Bass in the 1960s movie opening and end credits featured typography that was truly kinetic. The opening title sequence of North by Northwest, a piece created by Saul Bass contained animated text that “flew” in from off-screen and finally faded into the film itself. Temporal media allows for dramatisation of typographic content through motion that brings type to life. Unlike static media like print, which allows only for creating an illusion of motion, in kinetic typography, expressivity can be achieved by manipulating typographic attributes over time.

Typographers soon realised that the language of typography derived from its origin in static media was no longer adequate to articulate temporal forms. The study of temporal typography began in earnest with several classification schemes and terminology proposed by researchers like Yin Yin Wong and Barbara Brownie. One such example is the distinction between form and identity seen in examples of fluid typography, a term coined by Brownie. Describing the holographic poetry of Eduardo Kac, Brownie observes that,

A fluid form can evolve over time to the extent that its meaning also changes. A single form may be observed in one moment as having one verbal identity, and in another moment, once it has transformed, as presenting another identity.

In contemporary times, a similar change in the landscape of media has come about with the rise in digital devices that allow readers to directly interact with and manipulate typographic forms. If the time-varying characteristics are considered the essence of temporal media, the new affordance brought about by digital media is interactivity. This new design opportunity for using interactive medium of presentation was explored early by pioneers like Muriel Cooper in her interactive, three-dimensional presentation of text in Information Landscapes at the MIT Visible Language Workshop.

The nature and evolution of media

One way to tease apart the role of media in typography is to study the general nature and evolution of any communication medium. Marshall McLuhan, in his classic analysis, noted that the medium through which we choose to communicate holds as much, if not more, value than the message — hence his famous quote “the medium is the message”. McLuhan saw media as an extension of the self, a technology that extends natural human abilities to think, feel and act. Every new medium brings with it, a psychological, physical and social impact on the ways in which we perceive and process information.

One such characteristic of media’s evolution is the phenomenon of newer media subsuming the functionality of older media. Jason Lewis, in his thesis on Dynamic Poetry, observes that “it took several decades for film to fully separate itself from theatre and photography, and much later, for video to separate itself from film”. Consequently, during the initial development of any media, there is a period of time in which designers rely on paradigms and terminology of previous media, a phenomenon Lewis terms as content-lag.

As designers get more familiar with the unique design opportunities in a medium, there’s a development of an aesthetic native to the medium and conceptual frameworks specially suited to exploit those opportunities. Continuing with the example of typography in film, separation of film from older forms of media, led to the pioneering works by Saul Bass and others and the subsequent academic study of kinetic and fluid typography.

Media and affordances

As McLuhan noted, every media bring changes to the way we perceive and process information. When a new medium is still in its infancy, it is difficult to separate the essence of the medium from its rapid technological advances. Put another way, every media offers new affordances for the design of new typographic forms. Static media allowed designers to experiment with fixed attributes of form, colour and layout. Temporal media introduced a new affordance of time allowing these static typographic attributes to change and evolve dynamically. Similarly, the essence of interactive media is its ability to respond to the reader’s action, i.e., interactive media affords typographic forms to actively interact with readers. In every mature medium, typography adapts to the affordances particular to that medium and hence develops a native aesthetic which cannot be replicated in previous media.