Computational Poetics & Interactivity

Nature of interactivity

Since interactivity is the defining characteristic of digital media, it is important to identify and classify different forms of interactivity. Wong in her seminal thesis [1] on Temporal Typography defines interaction as any form of user control in a presentation. Furthermore, she considers any typographic artefact with a predefined presentation sequence as a form of passive interaction. Examples of kinetic typography that are consumed in a linear way by the reader fall into this category. If the reader has non linear access to a presentation sequence — for instance, with a time slider — then the presentation is considered to exhibit active interaction. It is important to note that per Wong’s classification, all static and temporal media exhibit passive interaction, while only interactive media may potentially exploit active interaction.

John Maeda in a series of articles called Metadesigning took a slightly different approach to teasing apart the fundamental vocabulary of interaction. After experimenting with graphics that change with time, Maeda expanded his scope to what he called “reactive graphics” or “visual experiences that respond to user input in real-time”. The core properties of a reactive graphic is a set of actions that the piece provides to the user, who upon acting on one of these actions sees an immediate response.

Jim Campbell further classifies [2] “reactive graphics” distinguishing controllable systems from responsive systems. A controllable system is akin to a monologue or a command-and-comply system common in traditional graphical user interfaces where the user issues a command and the system complies by acting in response. In a truly reactive system, this flow of communication is two-way with both the user and system continuously reacting and responding to each other. This classification is evocative of Chris Crawford’s definition of interactivity as dialogue.

Interaction: a cyclic process in which two actors alternately listen, think, and speak.

Building on the idea of interaction as dialogue, Jason Lewis proposed his classification [4] of interactive typography. This framework focuses on two key ideas: dynamics, which relate to how the medium presents change, and response, which relates to how the reader interacts. On screen, typographic objects can be both dynamic and responsive.

The dynamics of an object can be further broken down into constructive, reactive, active or static. A static object does not change with time or respond to the user, while an active object changes its appearance over time independent of any user actions. Based on this terminology we may say that static typographic forms consist of purely static objects while temporal typographic forms may include both static and active objects. A reactive object, on the other hand, responds to the reader’s actions while maintaining its composition. A piece of type that can be zoomed in or out by the user is an example of reactive dynamics. A constructive object is the most complex of all four dynamics and can respond to reader’s action changing both its form and composition. The interaction between a constructive object and the reader can be characterised as a constant exchange of information.

Response captures the reader’s view of the system and describes how the dynamics of a piece of type is initiated or maintained. Depending on how elements respond to the reader’s input, Lewis further classifies element responses as dependent (dependent solely on the reader’s input), independent (elements change independent of the reader’s input), hybrid (elements combine both dependent and independent change) and non-responsive (elements do not change at all).

Role of computation

Technology bring out not only evolution in the presentation medium but also changes in the tools used by designer to create typographic artefacts. Introduction of digital type design and composition tools changed the design process with the proliferation of personal computers in the late 20th century, taking over the creation of static, and later temporal typographic forms.

Interactive typography poses a challenge to contemporary designers as digital design tools have not evolved to allow for the creation of custom interactions on top of type. In 1995, John Maeda moved away from the existing crop of design tools and began exploring “digital graphic design not as a printed image but as computer programs”. This trend of using computer code to create interactive typography exploded with the creation of computer languages aimed towards designers, such as Maeda’s Design By Numbers (1999) and Casey Reas and Ben Fry’s Processing programming language (2001).

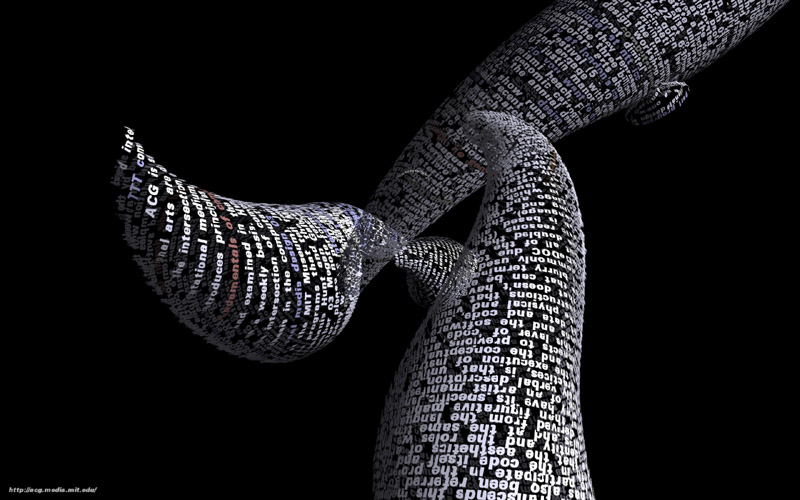

In the context of visual design, computation is a unique tool that allows drawing and manipulation of elements on a screen through a series programmable instructions fed to a computer. It’s important to note that computation is only a tool that affects the process of design while the final presentation medium of the artefact may still be print, animation or any interactive surface. Casey Reas considers software as a “unique medium with unique qualities”. Ideas that are not easily expressible in other media can be expressed through code. In defence of software as a creative medium, he states that,

For many decades, computers have been more than enhanced calculators. They are media machines, they are imagination engines, computers are tools for thought, and they are design machines. Computers are a unique and emerging medium for the visual arts.

An interesting analogy may be made to the creation of video games. Video games encompass all possible media (from visual, sound and animation to interaction design) and making digital games necessitates a fluency with code. Making games is difficult, but the results are inarguably engaging and inspiring. Throughout history, designers have always embraced new technology — from the printing press to digital typesetting — changing and refining their process to get more out of typography. In the end, the question of whether designers should code, boils down to motivation.

After the dawn of the electronic age, with the creation of digital design tools, poetics has become the practice of synthesising various media like sound, video, motion and interaction into a singular, harmonious experience. This rapid change from poetry captured on a printed page to poetry built into and experienced in a mediated space is aptly described by David Johnston in his book Aesthetic Animism.

Poems are manipulated and printed in 3-D, on websites, in virtual environments, as installations, and augmented reality. The page becomes vestigial; the screen dominates for a while; and now we are entering an era of mediated things, poetic objects, and poetic organisms.